Orthodontic Practice US Magazine

By Dr. Ronald Cohen

Dr. Ronald Cohen explores a systematic approach to a painful disorder of the head and neck before orthodontic therapy.

Dentomandibular sensorimotor dysfunction (DMSD) is a frequently painful disorder of the head and neck, temporomandibular joints (TMJ), jaw function, and dental forces. The force distortion causing DMSD may adversely impact the long term stability and reliability of dental restorations and adaptations that patients have received for unrelated conditions. A thorough knowledge of the problems and a comprehensive assessment/treatment approach with which to resolve them are pivotal to helping orthodontists and general dentists ensure the integrity of natural teeth and current and future dental work, as well as minimize or eliminate pain and other negative symptoms. This article discusses dentomandibular sensorimotor dysfunction and demonstrates a case in which a systematic approach to its treatment was undertaken prior to initiating orthodontic therapy.

Introduction

Dentomandibular sensorimotor dysfunction (DMSD) is a frequently painful disorder of the head and neck, temporomandibular joints (TMJ), jaw function, and dental forces. It stems from misalignments in the physiology of the skull and mandible that result in problems with bite force, muscle movement, and/or balance of joints, leading patients to experience extreme amounts of force or improper/unbalanced dental forces.1,2

Individuals with force issues — many of whom might not even realize that their conditions stem from DMSD or that dentists can provide effective treatment for it — suffer from many diverse symptoms. Those that directly impact the teeth and mandible include abfraction, bruxism, tooth erosion, fracture, or damage; instability in the dental arch form; jaw clenching (with or without the formation of a torus); temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD); and clicking and popping of the jaw. Other seemingly disparate, yet highly disruptive symptoms associated with DMSD, include chronic headaches and migraines, sleep disorders, tinnitus, myofascial pain, poor airway issues, compensatory adaptations in posture, and limited range of motion.1-3

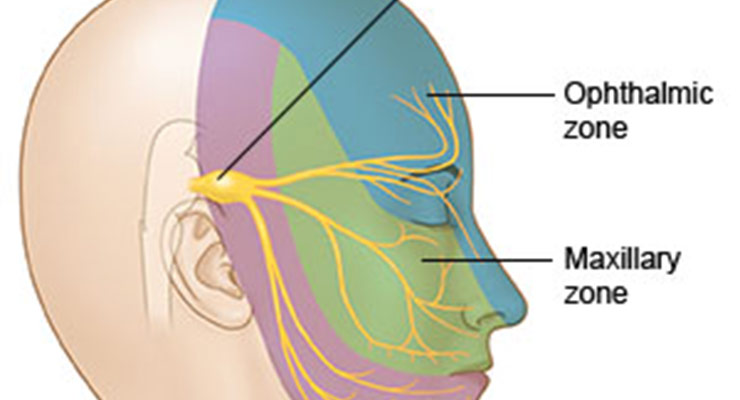

Physiologic interconnections also contribute to complications in understanding, assessing, and treating this complex condition. For instance, although DMSD is not the sole trigger of migraines — hormones, sleep problems, nutrition, and other factors may play a role as well — its connection to the trigeminal nerve is thought to be a likely contributor to many cases of migraines. The trigeminal nerve generates impulses that cause blood vessels on the brain to swell, thus transmitting pain messages to the brainstem.4

Patients with DMSD, and dentists seeking to treat the condition’s complications, may encounter other challenges as well. For example, force distortion may adversely impact the long-term stability and reliability of dental restorations and adaptations that patients have received for unrelated conditions. This will necessitate additional treatment to achieve optimal function and to protect dental interventions from irregular forces.1,2

Prevalence of and problems to treating related conditions

These often debilitating conditions, outcomes, and complications are not isolated cases affecting a relative few. According to the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the number of Americans who suffer from TMJ and associated problems may range from 10 to 45 million individuals,5 and when the number includes those suffering from tinnitus and other conditions, the number rises to an estimated 80 million people. Even more prevalent and impactful, approximately 90% of the U.S. population has headaches, and individuals who suffer from migraines—estimated at more than 29 million Americans — lose between 157 million days of work and school annually.6 Research indicates that up to 80% of headaches result from some type of dental force-related problem.

There are many aspects to understanding and treating DMSD related conditions. For effective, long lasting, and predictable results to be achieved, it is imperative that healthcare professionals and their patients understand DMSD; why it occurs; its not-always readily- apparent connections to other physiologic components and factors; the importance of properly diagnosing and treating it; the most effective methods/ protocols for assessing and treating it; and who is best equipped to provide such assessment and treatment. Unless DMSD is properly addressed, a patient’s condition will not improve; rather it will worsen and likely become chronic, and existing and future dental restorations may consequently fail. A thorough knowledge of the problems and a comprehensive assessment/treatment approach with which to resolve them are pivotal to helping orthodontists and general dentists ensure the integrity of natural teeth and current and future dental work, as well as minimize or eliminate pain and other negative symptoms.

Until recently, healthcare professionals who sought to help patients address their DMSD-related distress faced numerous obstacles. Many patients, ignorant of the cause of their problems and having exhausted over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription medications, as well as non-pharmacological options, such as physical medicine,6 abandoned their search for solutions and resigned themselves to enduring lives of chronic pain and diminished quality of life. Of those individuals who persisted in seeking help, typically only one in five sought out a physician’s assistance after having no success with OTC remedies.5 Orthodontists and general dentists, in particular, have largely been overlooked in favor of physician-based healthcare providers and chiropractors, who are more likely to be considered “headache/migraine experts” by the public. Additionally, dental professionals and their teams lacked an integrated system and the training necessary to provide complete care for DMSD-related cases.

Why Dentists are Uniquely Suited

Orthodontists and general dentists, recognized experts in oral health, also are knowledgeable about and trained in managing the muscular and nervous components of the jaw, neck, and head, according to the American Dental Association. As such, dental professionals can take a leading role in treating issues relating to DMSD, TMJ, and associated problems.8,9 Incorporating a system for assessing and treating improper dental forces that cause painful conditions in the mouth, head, face, and neck areas represents an exciting and significant opportunity for dentists to be of service to their patients while also benefiting their dental teams and practices. Those who elect to offer patients assessment and treatment for DMSD and associated conditions have a competitive edge, distinguishing themselves, their dental teams, and practices as comprehensive providers of an array of overall health services in the convenience of a practice they’re already familiar with.

This patient- and practice-enhancing opportunity is possible through the use of a state-of-the-art proprietary system (TruDenta, National Dental Systems, LLC, TruDenta.com). The only comprehensive approach to the assessment, treatment, and resolution of DMSD conditions, it offers orthodontists and general dentists a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared, conservative care strategy that can be customized for managing pain and inflammation, restoring range of motion and function, and reestablishing stabilization to the mouth, jaw and head.

Dentists and dental teams who add TruDenta capabilities to their practices are uniquely trained and equipped to offer their existing patients complete care from professionals they already know and trust, as well as attract new patients by establishing themselves as experts in providing a proven assessment and therapy that employs objective and subjective methods and state-of-the-art technologies found in less than 1% of all dental offices in the United States today.10 These combine to enable them to comprehensively assess, treat, and manage/monitor patients’ chronic headache and face, TMJ/D, neck, and other head area pain, as well as other dental force-related conditions.

Case Presentation

The case that follows demonstrates the straightforward manner in which the TruDenta system enables orthodontists and their teams to achieve successful treatment and rehabilitation outcomes through a compelling visual and objective assessment, as well as scientifically based, systematic, and predictable treatment methods and technologies derived from sports medicine to offer a customized pathway of care.

A 21-year-old woman presented complaining of soreness of the mouth and jaws due to clenching and grinding. The patient received a complete examination that included a head health, medical, and headache history, and a pharmacological assessment. Dental, periodontal, airway, orthodontic, and occlusal examinations also were undertaken.

The patient showed symptoms of muscle pain and headache pains. She claimed pain in the jaw joint, ear, and side of the face. There was a history of popping and clicking, and headaches on the side of the head. She claimed tightness of the jaws in the morning, and that her jaws became tired when chewing. There was history of soreness in the eye and ear areas, as well as neck and shoulder pain. She indicated that she experienced the pain daily, and that she was tired of it. Fortunately, she had no history of previous treatment for this condition, something that is rare in stomatognathic patients, since many have tried myriad treatments and healthcare professionals prior to seeing orthodontists. The patient reported that she regularly took Excedrin, Tylenol, and Allegra-D to combat her symptoms, but that they were becoming unmanageable with those medications.

Upon palpation, the patient showed 6/10 tenderness to palpation of the lateral pterygoinds, masseter muscles, temporalis tendons, and right posterior belly of the temporalis with trigger points. Additionally, she showed 7/10 in the right SCM and bilateral occipital insertion of the trapezius muscles. Her opening range of motion was restricted to 42 mm, with a deviation to the right and a restricted right range of motion as well. Diagnostics included cephalgia 784.0, muscle spasm 728.85, and headache 339.1.

Crucial to establishing the severity of sensorimotor dysfunction, any abnormal, excessive, or imbalanced forces were identified objectively using mandibular range of motion (ROM) disability, cervical range of motion disability (digitally), and digital force analysis (T-Scan). The ROM portion of the diagnostic process provides objective data conforming to American Medical Association (AMA) guidelines (Figure 1).

The patient’s T-Scan testing showed significant anterior prematurity with heavy force values (Figure 2). This was further confirmed by cone beam CT generated corrected tomograms, which proved distally trapped condyles due to occlusal forces and positions (Figures 3 and 4). Clench T-Scan demonstrated further the extent of the anterior prematurity and the significance of the resulting condylar position (Figures 5 and 6).

Treatment Protocol

Treatment was planned to achieve relief of the neuromuscular problems as documented, followed by alignment and balancing of the mandible, dentition, and force values, as well as alleviate pain. Treatment recommendations consisted of office visits, manual muscle testing, ROM testing, TMJ ultrasound, applied electrical stimulation, manual muscle therapy, cold laser therapy, therapeutic exercises, home care instructions, occlusal analysis, occlusal orthopedic device (NU modifier), and self-care home management training.

Stabilization goals included orthodontic therapy utilizing SureSmile® (OraMetrix) advanced 3D technology once muscle stability was achieved. Diagnostic simulations indicated that lower incisor extraction was indicated to allow elimination of anterior dental prematurities and forward positioning of the condyles. Once achieved, equilibration would be undertaken to stabilize the dental forces within the new balanced stomatognathic envelope.

Treatment Outcome

The patient’s treatment consisted of five weekly in-office visits of therapeutic rehabilitation using cold laser therapy, ultrasound therapy, low-level electrical current stimulation, and manual muscle therapy. A custom rehabilitation orthotic for the mouth was also worn at home until we began the maxillary orthodontic treatment.

At 5 weeks, the patient’s condition had improved sufficiently so that orthodontic therapy could begin in order to eliminate the obvious dental deflective interferences (Figures 1, 7, and 8). Extraction of tooth No. 24 and placement of full fixed orthodontic appliances occurred in February 2012 (Figure 9). The SureSmile therapeutic scan was made in June 2012 so that the final plan could be fabricated virtually (Figure 10), and the robotic wires were prescribed to finalize her case. A total of three prescription wires were delivered, and the patient was debonded in January 2013, for a total orthodontic treatment time of 11 months (Figures 11 and 12).

Dental bite force balance was confirmed at her immediate post-treatment conference in February 2013 with the T-Scan and ROM analysis, which revealed virtually normal ROM measurements and significantly lessened anterior prematurity (Figures 1, 13, and 14). We have equilibrated once so far, and she is scheduled to finalize her equilibration at her next appointment, with additional follow-up T Scans to verify force balance (Figures 15-17). The patient reports a much improved sense of her teeth “fitting together,” no muscle spasms or headaches, and an incredibly positive experience with her treatment.

Conclusion

With the acceptance and incorporation of a comprehensive assessment and treatment system, orthodontic practices have the opportunity to expand the scope of services they provide to patients looking to resolve the TMJ/D and head pain issues associated with dental force related problems. The proprietary TruDenta system, which incorporates assessment devices and therapeutic technology derived from sports medicine, uniquely empowers orthodontists to offer a proven, long-term solution and customized pathway to care for DMSD-related conditions.

Treating patients with TruDenta is straightforward; treatments are simple, quick, effective, painless, and require no drugs or needles. Many dental practices offering the TruDenta pathway to care — including orthodontic practices — have reported that, within a 10- to 12-week period, their patients experienced life altering relief from their chronic pain.

Additionally, it now gives us the ability to properly balance our finished orthodontic cases like never before. The combination of SureSmile virtual diagnostic and robotic treatment, and TruDenta force value detailing finally gives us the tools to perfectly finish our cases for maximum stomatognathic function and stability. It’s a dream that has finally become a reality.

Add TruDenta to Your Orthodontic Practice and give patients another reason to smile. For more information, call 1-855-770-4002.

References

- Junge D. Oral Sensorimotor Function. Medico Dental Media International, Inc.: 1998.

- Sessle BJ. Mechanisms of oral somatosensory and motor functions and their clinical correlates. J Oral Rehabil. 2006;33(4):243-261.

- Okeson JP. Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion. 6th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2008.

- US News Health. Headache. US News and World Report. 2006. Accessed July 3, 2012.

https://www.usnews.com/healthconditions/brain-health/headache - Adults. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Web site. Accessed December 7, 2012.

https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/adults - Migraine. National Headache Foundation Web site. Accessed July 3, 2012.

https://headaches.org/2012/10/25/migraine/ - Ostler GL. Building professional referral relationships with physicians. Dental Economics. 2012. Accessed July 3, 2012.

http://www.dentaleconomics.com/articles/print/volume-96/issue-12/features/buildingprofessional-referral-relationshipswith-physicians.html - Sardella A, Demarosi F, Lodi G, Canegallo L, Rimondini L, Carrassi A. Accuracy of referrals to a specialist oral medicine unit by general medical and dental practitioners and the educational implications. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(4):487-491.

- Dentists: Doctors of Oral Health. American Dental Association Web site. Accessed July 3, 2012.

http://www.ada.org/4504.aspx - TruDenta. Accessed January 22, 2013.

https://trudenta.com/